29/05/2021

The causes of economic growth are a strongly debated topic among economists, international organisations, and governments. Some countries have benefited from high economic growth in recent decades, namely the 'East Asian miracle' countries – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Several studies argue that luck plays a central role in economic growth, as uncontrollable conditions such as climate, location, and vulnerability to natural disasters have a large impact on the growth potential of a country. On the other hand, some studies argue that good luck is a function of good policy and that countries ultimately need the appropriate policies to succeed. Though luck may not play a fundamental role in economic growth, developed countries should do more to help those who have suffered from uncontrollable events.

Is economic growth lucky?

Economic growth is partly subject to the natural conditions of a country. High levels of economic activity are typically found near coastlines because of cheaper and easier access to international trade. The burgeoning Chinese cities of Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou – three out of the four cities with the highest GDP in the country – are all found on the coast. Landlocked countries with high temperatures and volatile rainfall are more likely to be poor. On the other hand, countries such as the UK that benefit from high rainfall, mild temperature, and easy access to oceanic trade are more likely to achieve high growth rates. Indeed, the UK was the wealthiest country in the world in the 18th and 19th century. Today, the countries that are still developing are typically the countries that are vulnerable to environmental volatility. And as developing countries are highly reliant on environment-dependent agriculture, they often experience volatile growth rates, further reducing their chance of achieving economic stability.

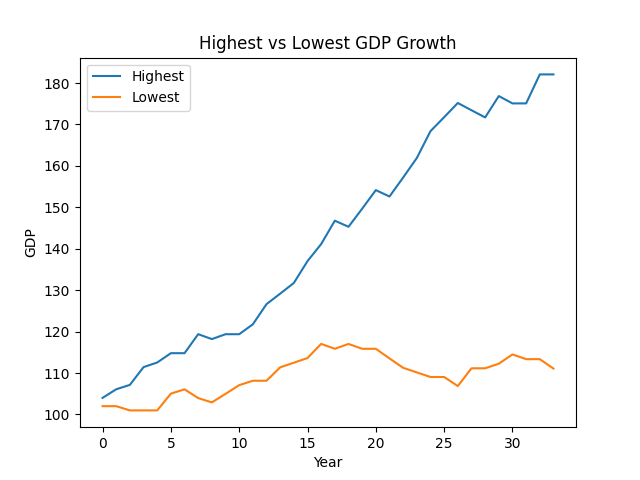

Not only do the natural conditions of a country contribute to economic growth but also their vulnerability to natural disasters and shocks. According to William Easterly’s book The Elusive Quest for Growth, poor countries accounted for 94% of major natural disasters and 97% of natural disaster-related deaths from 1990 to 1998. The high susceptibility to shocks in developing countries may explain their volatile growth rates. Gabon, a country vulnerable to natural disasters, had one of the highest GDP growth rates in the world from 1960 to 1975 followed by negative growth in the subsequent 15 years. The poorest 15 countries in 1960 had growth rates ranging widely from -2% to 4% until 1994. Figure 1 shows a graph, created using a computer program, that displays the long-term impact of random economic growth on GDP. This program runs through 34 years of randomly selected growth rates from between -2% to 4% for 15 countries and then plots the highest and lowest GDP out of those countries at the end of the period. Though economic growth is not completely random, the graph is useful in showing the potential long-term impact of luck on GDP.

View the code for this graph here. Created by Joshua Kenyon.

Moreover, countries in the early stage of development are limited in the number of economic projects that they can invest in. The lack of diversification in their economies often leads to unpredictable growth rates, with countries that ‘bet on the right horse’ growing faster than others. Some studies argue that the East Asia miracle countries have been the recipient of such luck. Singapore’s GDP per capita, for example, increased from 20% of that of the USA’s in 1960 to 88% by 2000. This can be partly attributed to Singapore’s production of electronics. By the late 1980s, this was Singapore’s largest industry in terms of jobs and manufacturing output. Singapore may not have been so successful had it invested in a less profitable industry or had the electronics industry not boomed.

Good policies are crucial for economic growth

Some economists dispute that the East Asian countries were lucky, but rather that they enacted good policies that caused economic growth. In his book Bad Samaritans, Ha-Joon Chang argues that these countries used controlled foreign direct investment to allow domestic industries to succeed. Before 1963 in Japan, for example, foreign ownership was limited to 49% whilst in ‘vital’ industries foreign investment was banned altogether. Moreover, Taiwan had a strategy of using its state-owned enterprises to provide the private sector with cheap, high-quality inputs, giving the private sector an advantage in global trade. These policies played a crucial role in facilitating high growth rates in East Asia. And though good fortune may have played a part, it would be inaccurate to claim that these countries grew by chance and not by good policymaking.

The burgeoning city of Tokyo, Japan. Photo credit: Steffen Zimmermann from Pixabay

The 2008 financial crisis had a large impact on the global economy. Some countries, however, suffered less than others. China’s growth did not fall below 6%, whereas Japan, Mexico, and the UK suffered annual contractions of between 5% to 10%. The countries that performed better often had good policies such as lower loan-to-deposit ratios and higher foreign exchange reserves. Indonesia, for example, had a growth rate of 4.6% in 2009, compared to the European Union who suffered a -4.3% growth rate. One study argues that Indonesia was lucky in terms of having a relatively small export share to GDP, meaning they were less exposed to the global crash. However, the government of Indonesia and the Bank of Indonesia successfully took measures to mitigate the effect of the crisis. For example, they increased the confidence in the banking sector by raising the deposit guarantee ceiling from 100 million to 2 billion rupees per account. Besides that, they lowered the interest rate from 9.5% in November 2008 to 6.5% by the end of 2009, reducing the likelihood of corporate defaults. These measures gave rise to economic stability in Indonesia during a global crisis, suggesting that good policies are crucial for economic growth.

Though luck may explain why it is hard to predict which countries will achieve high growth rates and which will not, economic growth is not completely accidental. Luck may cause fluctuations around a long-term growth rate which is determined by more fundamental factors such as good government policies. Moreover, the argument that luck causes economic growth is unfalsifiable and may cause complacency in policymaking. Good luck can often be a consequence of good policy. As Thomas Jefferson once stated, “I am a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work, the more I have of it.”. The more countries ensure that they have the best policies to facilitate economic growth, the more luck they may benefit from. Developed countries should also acknowledge that bad luck can cause economic hardships in poorer countries, and act charitably to those who need financial assistance.